Evolution of an American Holiday

Today’s Thanksgiving holiday is an offshoot of three separate traditions.

One tradition is the harvest festival.

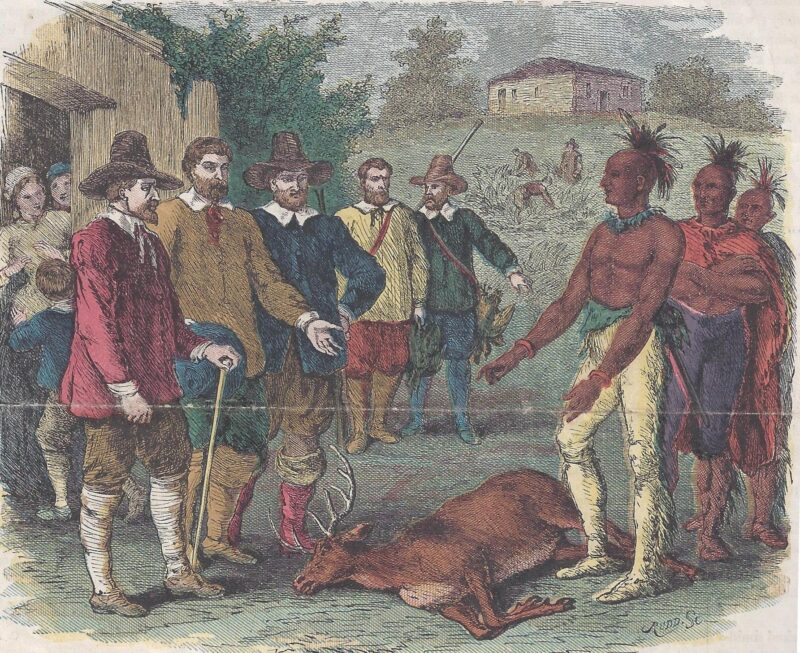

The event we call the “First Thanksgiving” at Plymouth, held by the Pilgrims and their Indigenous neighbors in 1621, was an informal harvest festival. While both the Pilgrims to God and the Wampanoag people to the Creator expressed thankfulness on a daily basis, this English festival was a secular celebration. It was, however, deeply influenced – as was every aspect of Pilgrim life – by their deep knowledge of, and regard for, Scripture.

The 1621 celebration was a one-time event. The colonists did not intend to establish an annual holiday and there was no official Thanksgiving proclamation.

The 1621 celebration is described in a letter written by Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow in December 1621, published the following year in London:

“… our harvest being gotten in, our Governour sent foure men on fowling, that so we might after a more speciall manner rejoyce together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours the foure in one day killed as much fowle, as with a little helpe beside, served the Company almost a weeke, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest King Massasoyt, with some nintie men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deere, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governour, and upon the Captaine, and others. And although it be not always so plentifull, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie.”

– A Relation or Journall of the beginning and proceedings of the English plantation setled at Plimoth in New England (London: Printed for John Bellamie, 1622), known as “Mourt’s Relation”

The second tradition from which our modern Thanksgiving has evolved is the Puritan religious “Day of Thanksgiving.”

Called by a religious leader in response to a special act of Divine Providence, these Days of Thanksgiving were purely religious and the entire day would have been spent in church, with no feasting or amusements. The first recorded religious Day of Thanksgiving in Plymouth Colony was held in 1623 in response to a providential rainfall. On November 15, 1636, Plymouth Colony enacted a law allowing the Governor and his Assistants to “command solemn days of humiliation by fasting, etc., and also for thanksgiving as occasion shall be offered.” (Plymouth Colony Records)

The third tradition is a special day of thanksgiving, called by a civic (not a religious) authority to celebrate a specific event, such as victory in battle or the end of a war.

King William and Queen Mary of England proclaimed a Thanksgiving for victory over the French. Their Thanksgiving was celebrated (like our modern Thanksgivings) on the 4th Thursday in November, November 26, 1691.

These three traditions gradually combined in colonial New England. The custom of religious and special days of thanksgiving evolved into a new annual event: a special day of both prayer and of feasting, celebrated in family groups, and proclaimed annually by the Governor in thanks for general well-being and a successful harvest.

The New England custom of an annual Thanksgiving celebrating abundance and family spread across America as the United States expanded westward. Some presidents proclaimed Thanksgivings, others did not. The tradition of a “civic Thanksgiving” to mark a special event also continued. In some years, particularly if there was a victory in battle as well as a successful harvest, there would be two Thanksgivings!

By the 1840s, most states and territories celebrated Thanksgiving, by proclamation of the individual Governors. Not all states celebrated Thanksgiving every year, however, and the dates on which it was celebrated varied widely from state to state.

In 1846, Sarah Josepha Hale, the influential editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, began an editorial campaign to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. Mrs. Hale was a native New Englander. She hoped that a national Thanksgiving would bring strengthen family ties and bring unity and moral strength to the country.

Mrs. Hale’s hopes for national unity were not realized. She continued her Thanksgiving campaign, however, and in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the first annual national Thanksgiving, calling for it to be observed on the last Thursday in November. Every President since has issued an annual Thanksgiving Proclamation.

The Thanksgiving holiday gained deeper meaning at a perilous time for the nation during the Civil War. Lincoln’s announcement of a national Thanksgiving in 1863 came at a critical point in the battle to save the Union. “In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity,“ Lincoln pointed to things that Americans could still be grateful for – that the country still survived, though in the throes of terrible conflict – that fields were still being plowed, ships still venturing at sea, factories still at work.

“It has seemed to me fit and proper,“ he declared, “that these blessings should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged, as with one heart and one voice, by the whole American people.”

Lincoln set aside the country’s seemingly insurmountable divisions and invited his “fellow citizens in every part of the United States to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens.”

It wasn’t the 1st national thanksgiving – other Presidents, including George Washington, had called for such observances before. But Lincoln’s proclamation had greater purpose– Thanksgiving was a way to unite a divided nation: “We fervently implore the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity, and union.”

The first annual national Thanksgiving was a means of bringing Americans closer together as a people, just as for so many generations the holiday had brought families together at the shared table.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Sarah Josepha Hale became one of the first popular figures to associate the holiday with early Plymouth Colony.

“The Pilgrim Fathers incorporated an early thanksgiving day among [their] moral influences… it blessed and beautified the homes it reached.”

– Sarah Josepha Hale, Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1865

Thanksgiving as an Annual Holiday: A Chronology

1621 First “Thanksgiving” (a secular harvest feast, not a religious Thanksgiving) at Plymouth. Other early “Thanksgivings” were held in Texas in 1541, St. Augustine in 1564, Maine in 1607 and Virginia in 1610 and 1619. These earlier events have no direct connection to the modern Thanksgiving holiday, which evolved in New England from traditions established in New England and eventually became associated with early Plymouth and the Pilgrims.

1623 Bradford proclaims Plymouth’s first religious Day of Thanksgiving as drought ends and the ship Anne is sighted.

1631 Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay proclaims a religious Day of Thanksgiving as a ship (thought lost at sea) arrives with food for the starving colony.

1668 Plymouth Colony proclaims its first Thanksgiving in gratitude for general blessings of the year: “The Court takeing notice of the goodnes of God to us in the continuance of our civill and religious liberties, the generall health that wee have enjoyed, and that it hath pleased God in some comfortable measure to blesse us in the fruites of the earth” asked the several religious congregations within Plymouth Colony to celebrate Thanksgiving jointly on the 25th of November 1668.

1777 First Thanksgiving proclaimed by national authority (Continental Congress) for all 13 states on December 18 (many states had individual Days of Thanksgiving earlier that year). The national Thanksgivings continued until 1784 and then stopped; the other states were resisting a “New England holiday.”

1789 A national Thanksgiving (but not an annual Thanksgiving) is proclaimed by President Washington. Of the early Presidents, only Washington, Adams and Madison declare individual Days of Thanksgiving. Annual Days of Thanksgiving are celebrated in individual New England states and begin to spread (to New York in 1817, Michigan in 1824, and Ohio in 1839).

1846 Sarah Josepha Hale begins her campaign in Godey’s Lady’s Book for a national annual Thanksgiving.

1863 Abraham Lincoln declares national Thanksgiving on last Thursday of November. There has been a national annual Thanksgiving Day ever since. It is still up to the state governors to also declare a Day of Thanksgiving. Not all have done so, and some have proclaimed their state’s Day of Thanksgiving on a different day than the national Thanksgiving.