Thanksgiving Menus

Thanksgiving “a la carte”

An exhibit celebrating the 100-year-old tradition of dining out at Thanksgiving

by Peggy M. Baker

Director & LIbrarian (Director Emerita)

Pilgrim Society & Pilgrim Hall Museum

An exhibit sponsored by the John Carver Inn and Hearth ‘n Kettle Restaurants

November-December 1998

From the elegant menus and haute cuisine of the gilded age hotel restaurant to the more “American” or homestyle cooking of the modern family restaurant, Thanksgiving menus tell the social history of Americans’ changing dining habits and their celebrations of Thanksgiving.

Some menus fill us with nostalgia for a splendid and leisurely time that can never be recaptured. Others give us ideas for our own Thanksgiving menus.

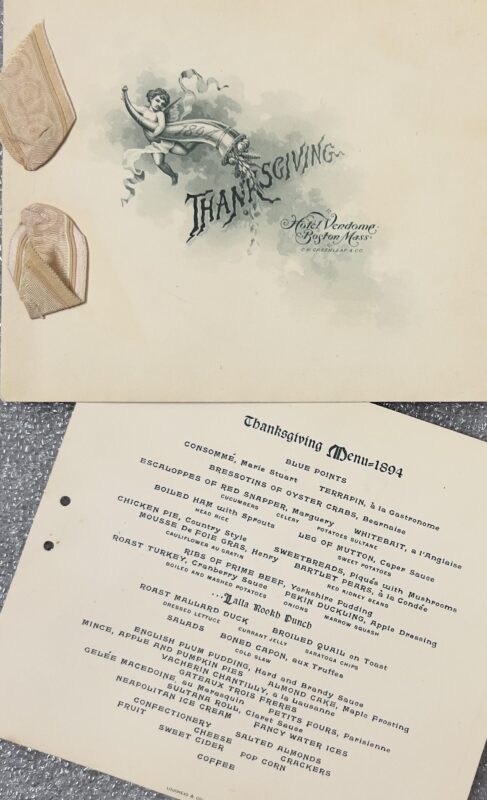

Some of the menus are memorable for their art as much as their food, with styles ranging from high Victorian Eastlake through Art Nouveau to the modern.

All of these widely varied menus can inspire us with their sheer exuberant love of life, food and the Thanksgiving holiday.

Imagine eating Thanksgiving dinner in an elegant “palace” hotel. A tuxedoed waiter bends to hand you a gold embossed menu, adorned with silk, listing a luxurious array of dishes. Starting, perhaps, with Terrapin a la Gastronome and ending with Vacherin Chantilly a la Lausanne, you leisurely enjoy a multicourse haute cuisine Thanksgiving dinner — including, of course, turkey with cranberry sauce, among a dozen other entrees. This could have been your Thanksgiving in the 1890s!

From the Waldorf-Astoria in New York to the Palmer House in Chicago, all across the nation, fine restaurant dining was the rage for the social elite and the upwardly mobile.

Now imagine fifty years later. . . your Thanksgiving dinner is very different. Featured are fruit cocktail, mashed turnips, and pumpkin pie, with nary a French sauce to be found! In 50 years, life — and the Thanksgiving bill of fare — have changed considerably. Three constants, however, still remain: the turkey with cranberry sauce, the decorative menu, and the hardworking creative chef working within the Thanksgiving tradition to produce a festive holiday meal.

What is a restaurant?

A restaurant is an eating establishment that offers choices in food, in prices, and in serving time. In early America, there were taverns, inns, coffeehouses, oyster houses, boarding houses and hotels serving meals, but no restaurants. The first American restaurant, Delmonico’s, opened in 1831 in New York City. From 1831 to the 1860s, a growing urban population supported a slowly expanding number of restaurants. Patrons were exclusively male.

After the Civil War, there was a burst of restaurants. More Americans had money and leisure, more Americans lived in cities. Some restaurants served Thanksgiving dinner, but the 1870s Thanksgiving was still a “home” occasion. Only an unfortunate bachelor would eat Thanksgiving dinner in a restaurant!

As the 1870s progressed, restaurants competed to provide ever more luxurious surroundings and abundant food. French cooking, originally introduced by Delmonico’s, reigned supreme. Elegant restaurants set the social standards for an upper class in search of refinement.

By 1880, women had begun to join their husbands and brothers at restaurants (although no lady would dine out without a male escort). Thanksgiving dinner at restaurants soon became acceptable, and then attractive.

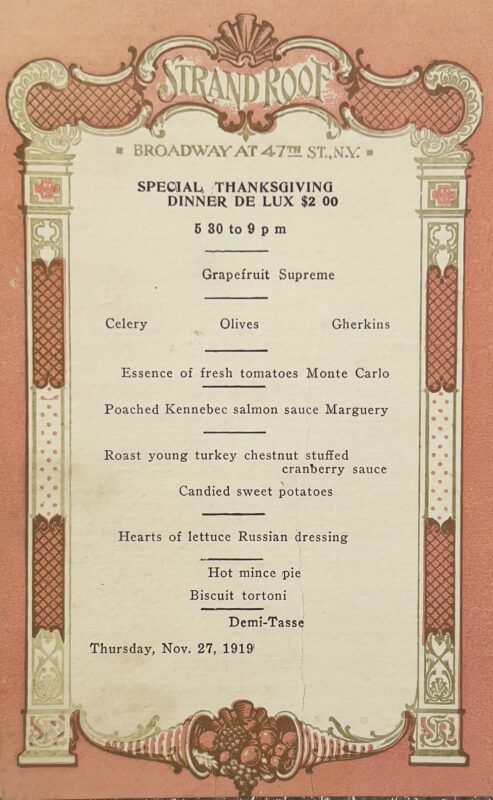

The Gilded Age of Restaurants

America’s gilded age, the 1890s to World War One, was the great era of restaurant cookery. Many restaurants were in grand new “palace” hotels, such as the Waldorf-Astoria. The quality of the chef was essential to the success of these grand restaurants. If the chef was good, charity benefits, family dinners and private parties of all sorts would be held at the restaurant. The 1890s and beyond was a time of lush and bounteous abundance, with an amazing volume of food in the Thanksgiving menu. By today’s standards, appetites and figures were both “overstuffed”!

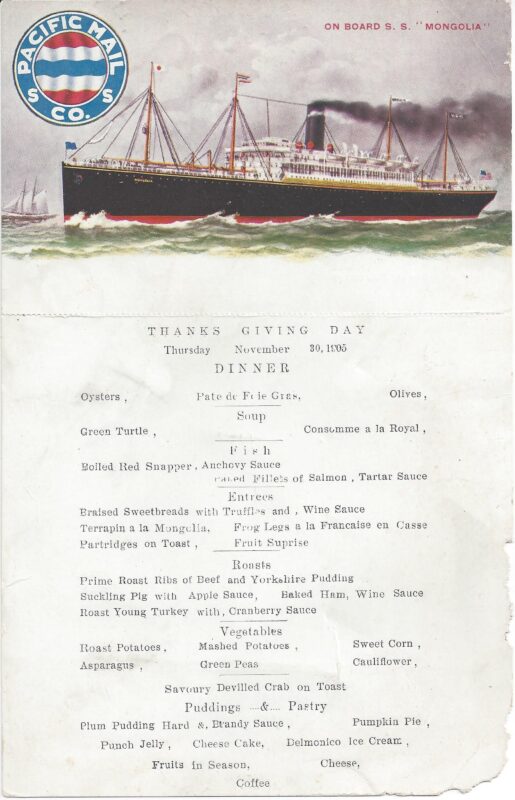

Thanksgiving Day Menu, S.S. Mongolia, 1905

Pilgrim Hall Museum, Baker Thanksgiving Collection

The Pacific Mail Steamship Company passenger and cargo liner, the S. S. Mongolia, built in 1904, served an elaborate Thanksgiving Day menu in 1905. From Pate de Foie to Delmonico Ice Cream, entrees included red snapper, sweetbreads, terrapin, partridges, frog legs, prime rib, suckling pig, ham and turkey.

Menus as Art

Hotel menus were the earliest bills of fare to be more than simple, disposable listings of specials of the day. For special occasions, such as Thanksgiving, hotels designed fantasy menus, using wonderful colors.

Menus could be fringed, embossed or textured, some using silks and ribbons. Many show great imagination and originality in terms of layout, illustration, and typeface.

Into the 20th Century

The early 20th century saw an interest in health, hygiene and nutrition. The discovery of “germs” in the 1880s, the “pure food” scares of the early 1900s, and research into vitamins (beginning in 1911) brought an emphasis on food that was sanitary and healthful.

The growing female workforce, and the scarcity of household help, led to food that was practical and easy. The move now was towards smaller meals and a simple, straightforward cuisine.

From Prohibition to Today

Fine dining, fueled by wine and liquor, was killed by Prohibition. Delmonico’s closed in 1923. The Waldorf survived only because hotel guests needed to be fed.

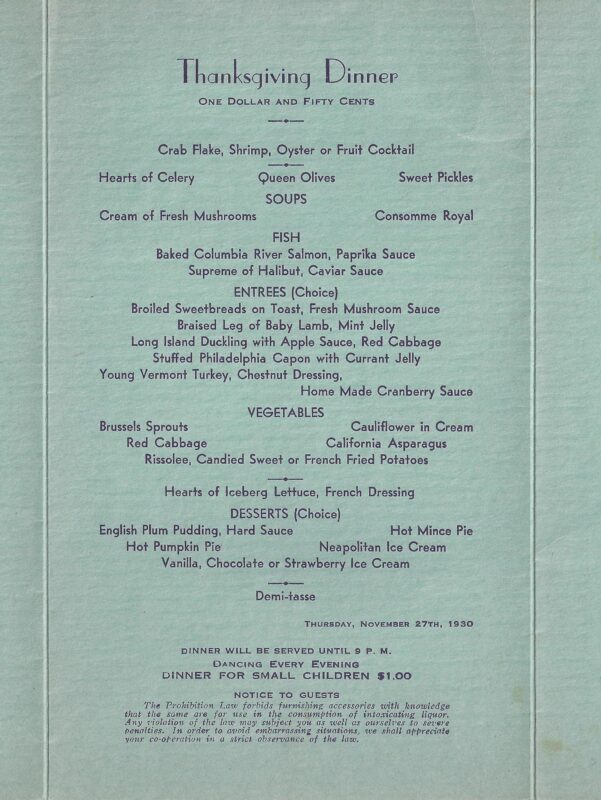

The 1930s saw a new type of restaurant — the family restaurant, serving basic, simple, wholesome, comfortably “American” food. Instead of haute cuisine, the 1930s restaurants provided a break from household chores and an opportunity to socialize.

In 1930, the Elks Club in Elmhurst, New York, offered an all American menu for $1.50. Entrees were Columbia River salmon, halibut, sweetbreads, lamb, Long Island duckling, Philadelphia capon, and Vermont turkey. The menu gave notice to guests that

“The Prohibition Law forbids furnishing accessories with knowledge that the same are for use in the consumption of intoxicating liquor. Any violation of the law may subject you as well as ourselves to severe penalties. In order to avoid embarrassing situations, we shall appreciate your cooperation in a strict observance of the law.”

The rebirth of haute cuisine began slowly, in 1941, with “Le Pavillon.” Staffed by refugees from war-torn Europe, Le Pavillon raised the level of sophistication of American restaurants by training a new generation of chefs. French terms and French sauces began to reappear on American Thanksgiving menus.

Thanksgiving Day Menu, Elks Club, Elmhurst, New York, 1930

Pilgrim Hall Museum, Baker Thanksgiving Collection

Ethnic restaurants are not a new phenomenon in America. The earliest group whose cuisine had an effect on restaurant cooking were the Germans in the 1850s, followed by the Chinese in the 1870s, the Italians in the 1880s, the Russians in the 1920s, and the Mexicans in the 1950s. (Because of its early supremacy, French cooking was never considered ethnic cooking.)

Ethnic restaurants blossomed with the adulthood of the baby boomers. They were well-educated and well traveled, open to new flavors, and took food authenticity seriously.

In 1997, Plymouth’s Sam Diego’s Restaurant served a traditional turkey dinner as well as “Hungry Pilgrim Burritos.”

“Influence of Chefs on Home Cooking

The elaborate restaurant cooking of the late 19th century influenced home cooking. For the middle class, home cooking became a complex art demanding considerable skill and, often, cooking classes.

From its opening in 1831 until its demise in 1923, Delmonico’s was responsible for nearly every innovative change in American dining habits.

Alessandro Filippini had been the Delmonico chef in the 1850s. In 1889, he published a cookbook, The Table, with recipes simplified from the actual Delmonico’s preparation. After Filippini left Delmonico’s in 1863, they hired a brilliant chef named Charles Ranhofer. In 1894, Ranhofer published The Epicurean, a monumental cookbook for professional chefs. It gives us a detailed guide to how food was prepared at Delmonico’s.

Below is a wonderfully lavish 1894 Thanksgiving Day restaurant menu from the Hotel Vendome in Boston, Massachusetts. This elaborate, “high Victorian” menu is coordinated with recipes from Filippini’s The Table and from Ranhofer’s The Epicurean.

See Thanksgiving Recipes for the highlighted 1890s recipes.

Thanksgiving Day Menu, Hotel Vendome, Boston, Massachusetts, 1894

Pilgrim Hall Museum, Baker Thanksgiving Collection

THANKSGIVING MENU 1894

Hotel Vendome, Boston

BLUE POINTS

CONSOMMÉ, Marie Stuart TERRAPIN, a la Gastronome

BRESSOTINS OF OYSTER CRABS, Bearnaise

ESCALOPPES OF RED SNAPPER, Marguery WHITEBAIT, a l’Anglaise

Cucumbers Celery Potatoes Sultane

BOILED HAM with Sprouts LEG OF MUTTON, Caper Sauce

Head Rice Sweet Potatoes

CHICKEN PIE, Country Style SWEETBREADS, Piqués with Mushrooms

MOUSSE De FOIE GRAS, Henry BARTLET PEARS, à la Condée

Cauliflower au Gratin Red Kidney Beans

RIBS OF PRIME BEEF, Yorkshire Pudding

ROAST TURKEY, Cranberry Sauce PEKIN DUCKLING, Apple Dressing

Boiled and Mashed Potatoes Onions Marrow Squash

ROAST MALLARD DUCK BROILED QUAIL on Toast

Dressed Lettuce Currant Jelly Saratoga Chips

SALADS BONED CAPON, aux Truffes

Cold Slaw

ENGLISH PLUM PUDDING, Hard and Brandy Sauce

MINCE, APPLE AND PUMPKIN PIES ALMOND CAKE, Maple Frosting

VACHERIN CHANTILLY, a la Lausanne

GATEAUX TROIS FRERES

GELÉE MACEDOINE au Marasquin PETITS FOURS, Parisienne

SULTANA ROLL, Claret Sauce

NEOPOLITAN ICE CREAM FANCY WATER ICES

CONFECTIONERY SALTED ALMONDS

FRUIT CHEESE CRACKERS

SWEET CIDER POP CORN

COFFEE