Myles Standish House Archeology

In 1856, James Hall performed the first professional archaeological excavation in Duxbury, Massachusetts at the exact location of the Myles Standish house. Hall recovered numerous artifacts from Standish’s land and even illustrated the site plan of Standish’s house. The plan and many of the artifacts have been in the collection of Pilgrim Hall Museum for over 150 years.

A descendant of Myles Standish, Hall was a steel-engraver in Boston by trade, with a professional eye for detail. He recorded his archeological activities with unusual precision for the time, noting where every artifact was found on a hand-drawn plot plan and identifying each item with its own label. Because of Hall’s meticulous approach, the Standish dig is considered one of the earliest professional archaeological excavations in the United States.

Hall was equally attentive to public interest and exhibited his findings to inquisitive visitors in a small hut he erected near the excavated Standish cellar hole. Two years after Hall’s project, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his paean to the Pilgrims, The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858), catapulting the Plymouth Colony soldier into national fame and memory. In 1859 and also in 1863, Hall placed most of his collection in the safekeeping of Pilgrim Hall Museum. His own descendant, aptly named Standish Hall, gifted additional materials in 1963.

The Standish archaeological site and collection date from ca.1630 to ca.1710. Hall’s original plan outlines a single structure with two narrow, elongated wings, which may have been subsequent structures. The building chronology is open to a range of interpretation, but the footprint could include Standish’s own early house with later additions or replacements by his children and grandchildren. From this multi-generational complex, Hall unearthed fragments of glass, broken pipe stems, bits of iron, and ceramic shards, reflecting the material culture and daily experience of the Standish household over an eighty-year span.

The assemblage encompasses recreational artifacts, cooking materials, weaponry, agricultural tools, and architectural materials. Though many are in poor and fragmentary condition, the objects evoke connections to the early Standishes and their world.

An iron element from a dog-lock musket not only reflects Myles Standish’s special role as military leader, but also the martial character of early colonial New England. Among Standish’s personal possessions inventoried after his death in 1656 were “one fowling peece 3 musketts 4 Carbines 2 smale guns, one old barrel,” and a sword and cutlass.

Book Clasp

PHM 114.8

An ornamented book clasp recovered from the site offers a different perspective of Myles Standish. As a man of learning, he left as part of his estate a library of nearly fifty published volumes on a wide range of topics. Standish’s reading encompassed works of history on Queen Elizabeth and the state of Europe, botanical studies by the Flemish physician Dodoens, Calvin’s Institutes, and classical works such as Homer’s Iliad and Caesar’s Commentaries. The book clasp would have been used to keep one of these valuable volumes closed when not being read, holding the pages together and preventing exposure to dust and moisture.

Further evidence of Standish’s literacy stems from his signature, recorded on several Plymouth Colony documents in the Museum collection. One document signed by Standish certifies the choice of Governor Bradford and Assistant Browne as representatives at Plymouth in 1647. (See Charles R. Strickland, “Recent Acquisition of Myles Standish Signature,” Plymouth Society Notes 5, 1955). Another Standish signature is found on a deed from 1655. In addition, a third signature exists in a book that is privately owned.

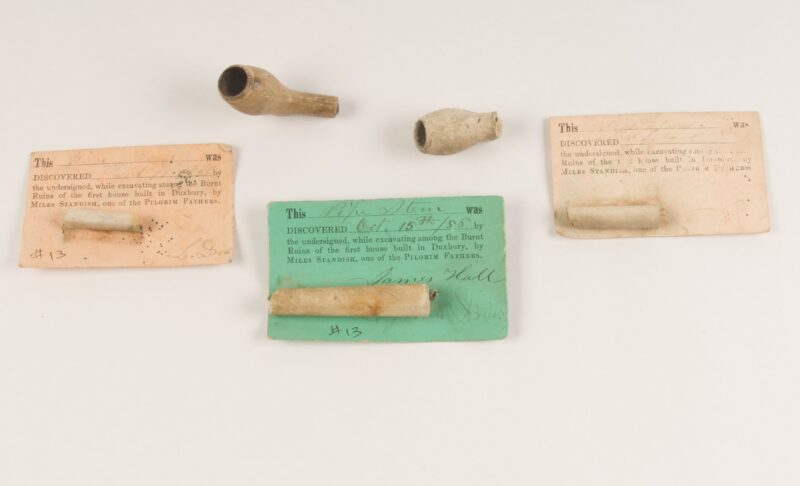

The archaeological collection appears to document Standish’s penchant for tobacco, a wildly popular consumable in late 16th-century England following the introduction of New World goods. Among numerous English pipe stems recovered from the Duxbury homesite is a fragment dating from 1590 to 1620, which may have been brought by Standish on the Mayflower.

Pipe Bowls and Stems

1635-1655

PHM 114, 2, 14, 19, 23

The clay pipe fragments from the Standish site were most likely made in England, since clay pipe making had not been established in the colony. The dates of the Standish pipes extend over a century, ranging from 1590 to 1710. Standish’s old homestead is known to have burned down around 1665. The presence of later pipe stems suggests that the area continued to be inhabited by descendants into the early 18th century.

Two corroded iron fragments speak to the particular experience of women in the Standish household. They are pieces of scissors or shears that were most likely used by Myles Standish’s “Dearly beloved wife Barbara,” their only daughter Loara, and possibly their daughter-in-law Mary Dingley Standish.

Very little is known about Barbara Standish. Her maiden name and family origins remain obscure, and even her death date, which occurred sometime after her husband’s, is uncertain. The rust-pocked Standish scissors indicate something of her life, however, as they were an essential tool for the needlework that was the responsibility of every colonial woman.

English girls were expected to learn sewing skills from childhood, and Barbara Standish almost certainly instructed her daughter in this area. In keeping with English tradition, Loara Standish demonstrated her proficiency in the needle arts by stitching a sampler, traditionally dated to 1653, just a couple of years before her death, when she was likely in her early twenties. Loara’s sampler, a masterpiece of early American decorative arts, is worked in red, green and blue silk threads on a linen field. It has been in the collection of Pilgrim Hall Museum since 1844, a generation before the acquisition of the Standish scissors that may have been used in the actual sampler’s making.

Piece by piece, the Standish collection of common household implements – bits of brass kettles, window glass, nails, and other fragments of daily life – provides an intimate look at early Plymouth Colony and the household of a significant colonial leader, Captain Myles Standish.

This content is based on research conducted for Pilgrim Hall Museum by Stephen O’Neill, former Associate Director/Curator, with portions drawn from a previously published article: Donna D. Curtin, “Unearthing the Standish Collection at Pilgrim Hall Museum,” The Society of Myles Standish Descendants Newsletter, Vol. 3 No. 1 (Summer 2018): 2-4.