History of Plymouth Rock

Current location of Plymouth Rock

Longitude = 70° 40′

Latitude = 41° 57′ 30″

Plymouth Rock is a granite boulder of the distinctive variety known as Dedham Granite, located on the Plymouth waterfront.

The visible top part of Plymouth Rock weighs approximately four tons. The larger bottom portion resting under the sand weighs approximately six tons. The Rock as it exists today is by many accounts considerably less than its original size.

The top portion of Plymouth Rock has been dragged around town, cracked, and chipped away by souvenir hunters over generations.

The base of Plymouth Rock has also been excavated and moved several times in the past 200 years, most notably in 1921 when it was repositioned beneath a new portico as part of Plymouth’s 300th anniversary celebration.

Plymouth Rock in the 17th Century

There are two primary sources written by the Pilgrims themselves describing their landing in Plymouth in 1620: William Bradford’s journal, Of Plymouth Plantation, and the 1622 account of the early colony popularly known as Mourt’s Relation. Both simply say that the Pilgrims landed. Neither mentions a rock in their account of the landing.

The first mention of a “Grat Rock” on the Plymouth waterfront appears in town records on February 16, 1715/16, when boundaries were being laid out for Water Street:

“… A Grat Rock yt lyeth below ye…sd Way from ye stone att ye foot of The hill Neere the Southerly Corner of John Wards land….”

– Records of the Town of Plymouth. Vol. 2 (1705-1743)

Plymouth: Avery & Doten, 1892, 151-152.

Sixty years after the first written record of a “Grat Rock” on the waterfront, the earliest reference to the tradition of Plymouth Rock as a landing place appears in print in 1775.

Plymouth Rock: Landing Place of the Pilgrims?

“It must be admitted at the outset that the claims and contentions that hover about the Rock can never be definitively addressed, due to unavoidable gaps in the historical evidence and inevitable differences in cultural perception.”

– James W. Baker, Plymouth Rock’s Own Story (The Pilgrim Society, 2020), 1.

The story of Plymouth Rock has roots in Plymouth’s oral tradition. James Thacher included an account of the Rock in his history of the town first published in 1832, over 200 years after the arrival of the Mayflower. According to Thacher, the original source of the Rock as a landing place was John Faunce, an English colonist who had arrived in Plymouth in 1623, through his son, Plymouth church elder Thomas Faunce.

“The Consecrated Rock. – The identical granite Rock, upon which the sea-wearied Pilgrims from the Mayflower first impressed their footsteps, has never been a subject of doubtful designation. The fact of its identity has been transmitted from father to son, particularly in the instance of Elder Faunce and his father, as would be the richest inheritance, by unquestionable tradition. About the year 1741, it was represented to Elder Faunce that a wharf was to be erected over the rock, which impressed his mind with deep concern, and excited a strong desire to take a last farewell of the cherished object. He was then ninety-five years old, and resided three miles from the place. A chair was procured, and the venerable man conveyed to the shore, where a number of the inhabitants were assembled to witness the patriarch’s benediction. Having pointed out the rock directly under the bank of Cole’s Hill, which his father had assured him was that, which had received the footsteps of our fathers on their first arrival, and which should be perpetuated to posterity, he bedewed it with his tears and bid to it an everlasting adieu. These facts were testified to by the late venerable Deacon Spooner, who was then a boy and was present on the interesting occasion. Tradition says that Elder Faunce was in the habit on every anniversary, of placing his children and grand-children on the rock, and conversing with them respecting their forefathers. Standing on this rock, therefore, we may fancy a magic power ushering us into the presence of our fathers. Where is the New Englander who would be willing to have that rock buried out of sight and forgotten? The hallowed associations which cluster around that precious memorial, inspire us with sentiments of the love of our country, and a sacred reverence for its primitive institutions.”

– James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth, (Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1835), 29-30.

In collecting the story of the Rock, Thacher took care to detail how the story was passed down over the generations through just four individuals:

John Faunce was born about 1608 and arrived in Plymouth about the age of fifteen in 1623 on the ship Anne, just three years after the Mayflower. Faunce would have personally known the surviving Mayflower passengers. He died in 1653 at about age 45, leaving his widow Patience Morton Faunce and seven living children.

Elder Thomas Faunce, son of John Faunce, was born in Plymouth about 1647. Growing up in early Plymouth, Thomas would also have personally known some of the surviving Mayflower passengers.

In 1741, the Elder publicly recounted the story of the Rock to his fellow townspeople, identifying it as the landing place of the first English settlers. Over 120 years had passed since the passengers came ashore, and Faunce wanted this landmark of the event to be remembered and to pass on information he had received from his own father. Thomas Faunce would have been only about six years old when his father died, but he had four older siblings who may have also been inheritors of the story. Faunce made a serious effort to communicate the story within his own family for many years. He died in 1745, just a few years after his dramatic visit to the shore to identify the Rock to a crowd of Plymouth residents.

Ephraim Spooner (1735-1818) was present at the 1741 event. His recollections of Elder Faunce’s plea for Plymouth Rock were from early childhood as he would only have been about 6 years old at the time. A lifelong Plymouth resident, Spooner was a successful merchant with a store on Main Street and a comfortable house on North Street, where he lived with his wife, Elizabeth Shurtleff. The couple had nine children, of which only four survived to adulthood. Spooner served as a Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, as Town Clerk for 52 years, and as deacon of First Church for 34 years.

Dr. James Thacher was born in Barnstable in 1754 and came of age during the critical years leading up to the American Revolution. In 1775, when he was 21 years old, he enlisted in the Continental Army as a surgeon’s mate and served throughout the war. After the war in 1783, he settled in Plymouth, where he opened a lucrative medical practice and also began to write.

He had far-ranging interests, especially in the areas of science and medicine, and published on a variety of subjects, including the Modern Practise of Physick in 1817, Observations on Hydrophobia in 1821, The American Orchardist in 1822, A Practical Treatise on the Management of Bees in 1829, and even an Essay on Demonology, Ghosts, Apparitions and Popular Superstitions in 1831. In 1823, Thacher published A Military Journal of the American Revolution, a richly detailed personal account of the war, based on the journal he kept as it happened.

Thacher was a cornerstone of local history, a founder of the Pilgrim Society and first Librarian and Keeper of the Cabinet at Pilgrim Hall Museum. In 1832, he published the first printed History of the Town of Plymouth, which he presented as “a minute narrative of the settlement of the oldest town in the New England territories.”

Thacher’s history of Plymouth is the first published account of the story of Plymouth Rock and what it symbolized to Plymouth residents in the late colonial era.

Plymouth Rock & the American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, several decades after Elder Faunce publicly shared his revelation about it to Plymouth townspeople, Plymouth Rock acquired both patriotic meaning and wider fame.

In 1774, local patriots “animated by the glorious spirit of liberty,” hitched up a team of oxen to drag the Rock up the hill to Town Square and deposit it next to the town’s liberty pole. In the process, the Rock split in half, impressing the crowd as a sign of America’s impending break with Great Britain.

“1774. – The inhabitants of the town, animated by the glorious spirit of liberty which pervaded the Province, and mindful of the precious relick of our forefathers, resolved to consecrate the rock on which they landed to the shrine of liberty. Col. Theophilus Cotton, and a large number of the inhabitants assembled, with about 30 yoke of oxen, for the purpose of its removal. The rock was elevated from its bed by means of large screws; and in attempting to mount it on the carriage, it split asunder, without any violence. As no one had observed a flaw, the circumstance occasioned some surprise. It is not strange that some of the patriots of the day should be disposed to indulge a little in superstition, when in favor of their good cause. The separation of the rock was construed to be ominous of a division of the British Empire. The question was now to be decided whether both parts should be removed, and being decided in the negative, the bottom part was dropped again into its original bed, where it still remains, a few inches above the surface of the earth, at the head of the wharf. The upper portion, weighing many tons, was conveyed to the liberty pole square, front of the meeting-house, where, we believe, waved over it a flag with the far-famed motto, ‘Liberty or death.’”

– James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth (Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1832), 201-202.

Just a year after its enthusiastic relocation next to the liberty pole, Plymouth Rock appeared in print for the first time.

In 1775, America had not yet proclaimed independence. War, however, was already being waged in New England. While there was not yet a formal “Navy,” George Washington had six small ships operating from Massachusetts Bay, intercepting supplies being sent by sea to British-occupied Boston. One of Washington’s schooners, the Harrison, captained by William Coit, was headquartered in Plymouth. In November of 1775, the Harrison captured two British ships with geese, chicken, sheep, cattle and hogs on board, heading from Nova Scotia to supply the British troops stationed in Boston. Coit’s triumphant return with his two prizes to Plymouth was reported in the Pennsylvania Journal of November 29, 1775:

“Captain Coit (a humorous genius) made the prisoners land upon the same rock our ancestors first trod when they landed in America, where they gave three cheers, and wished success to American arms.”

By the end of the 18th century, the Rock’s fame was widespread enough to be casually referenced in an influential Boston newspaper:

“The Federalists toasted their ancestors with the hope that the empire which sprung from their labors be as permanent as the rock of their landing.”

– Columbian Sentinel (December 22, 1798)

Plymouth Rock in the 19th Century

On July 4, 1834, after 60 years in Town Square, the top of the Rock – the portion hauled from the wharf to be set by the liberty pole –was moved down the road to Court Street and situated on the front lawn of Pilgrim Hall. The Pilgrim Society enclosed the Rock in an elaborate iron fence.

“It affords the highest satisfaction to announce that the long desired protection of the Forefathers’ rock is at length completed, and it may be pronounced a noble structure worthy of the purpose intended. The fabric is a perfect elipse [sic] 41 feet in circumference, consisting of wrought iron bars 5 feet high resting on a base of hammered granite. The heads of the perpendicular bars are harpoons and boat hooks alternately. The whole is embellished with emblematic figures of cast iron. The base of the railing is studded with emblems of marine shells, placed alternately reversed, having a striking effect. The upper part of the railing is encircled with the wreath of iron castings in imitation of heraldry curtains, with festoons; of these there are 41 bearing the names in bass relief of the 41 puritan fathers who signed the memorable compact while in the cabin of the Mayflower at Cape Cod in 1620. This noble acquisition reflects honor on all who have taken an interest in the undertaking. In the original design by George W. Brimmer Esq. ingeniousness and a fine taste is displayed; and in all its parts the work is executed with much judgment and skill. The castings are executed in the most improved style of the art. This superb memorial will last for ages, and the names and story of the great founders of our empire will be made familiar to the latest generation.”

– “The Forefathers Rock Enclosed,” Old Colony Memorial (Saturday, June 13, 1835), 2.

Meanwhile, the base of the Rock – the portion which had NOT been moved in 1774 — remained on the waterfront, embedded in Hedges Wharf and partly visible though the dirt covered planking.

Plymouth’s wharves were the center of activity for a busy commercial waterfront. The Pilgrim Society began buying portions of the wharf that contained the Rock base and surrounding buildings. The intent was to clear an area to formally display the Rock.

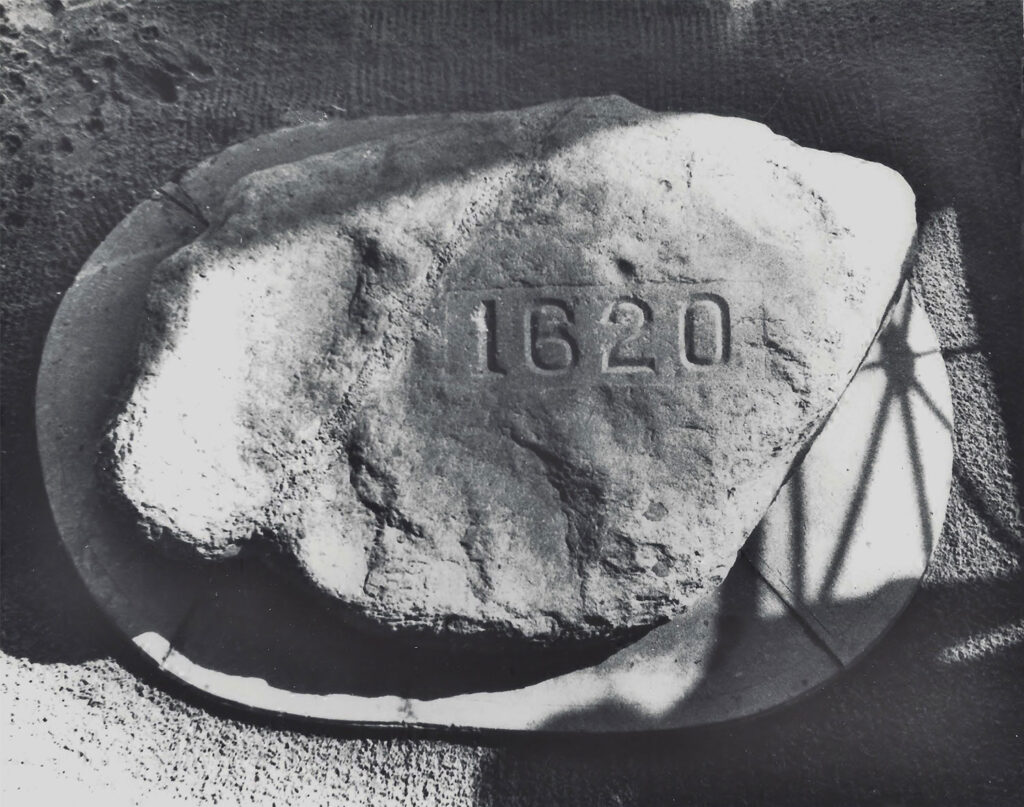

In 1859, the Pilgrim Society laid the cornerstone for a granite canopy to be built over the base of the Rock. The canopy, designed by Hammatt Billings, was finished in 1867. In 1880, the Pilgrim Society moved the top of the Rock from its location in front of Pilgrim Hall Museum and reunited it to the base of the Rock under the Canopy. It was at this time that the date “1620” was cut into the face of the boulder.

Plymouth Rock in the 20th Century

In preparation for the Tercentenary Celebration – the 300th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims – the entire waterfront of Plymouth was redesigned. By the early 20th century, commercial activity at the wharves had dwindled and some wharves were in disrepair.

The federal commission appointed to oversee the anniversary identified Plymouth Rock as a worthy project for improvement as “many thousands from every section of the United States” visited the Rock annually:

“It is suggested that the Nation is interested in having Plymouth Rock so located and surrounded as to provide in effect a shrine for the visitors of the future…”

– William Franklin Atwood, Pilgrim Plymouth Guide to Objects of Special Historic Interest … Together With a Brief Historical Outline of the Pilgrim Migration From the Inception of the Congregation At Scrooby, England, to the Permanent Settlement of Plymouth, Massachusetts. (Boston, Mass.: Blanchard Printing Company, 1921), 77.

The Pilgrim Society had already invested significantly in improving the Rock’s situation. The organization had not only managed to build a solid canopy, they had reunited both halves of the Rock beneath it. The Billings canopy displayed the Rock at street level, making the historic landmark accessible to visitors. Gates were added to the canopy to provide protection for the Rock, but these were left open during the day to allow sightseers to step inside the canopy and examine the Rock up close. Many visitors sat or stood on the Rock to pose for photographs.

Strangely, this rather charming example of Victorian monumental architecture was apparently despised within a generation of its being built. In 1889, when the National Forefather’s Monument, also designed by Billings, was dedicated, there was little praise or notice taken of the architect’s smaller canopy. Its small size seemed a disappointment, and there were complaints about the “bad” character of the waterfront district, with “ware houses, fishing vessels and ship chandler’s stores elbowing one another close to the sacred boulder.” [See “Faith crowns the Work! Completion and Dedication of the National Monument,” Old Colony Memorial (Saturday, August 3, 1889), 1].

In 1920, the federal commission described the Rock as “surrounded by unsightly buildings and piers which are used for commercial purposes.” The Billings canopy did not merit even a mention. [Report, Joint Special Committee on Pilgrim Tercentenary, February 28, 1920, in Atwood, 71.]

The care of Plymouth Rock was turned over to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the surrounding land was taken by eminent domain in a massive undertaking to recreate the Plymouth waterfront. The plan called for buildings and piers to be removed, the Billings Canopy demolished, the shoreline filled and reshaped, and Plymouth Rock lowered “as to permit approach to the rock by water, as was the case when the landing was made by the Pilgrims in 1620.” [Atwood]

According to the local paper, after the Billings canopy was removed, it was “dumped in two parts of the town, the stones more or less chipped in the process” and ended up “simply so much refuse stone,” to be re-used piecemeal in new construction if “it may be made to meet the requirements of modern days.” It was probably fortunate that the architect was dead by this time. [“Another Memorial Dedicated,” Old Colony Memorial, Vol. 100, No. 48 (December 2, 1921), p. 1.]

On December 20, 1920, Plymouth Rock was excavated and temporarily relocated while the old wharves were destroyed and the shoreline rebuilt in preparation for its new location.

An account of the moving of Plymouth Rock described how the top portion was raised by steam crane, swung a few feet over and laid down “on some of the rubbish left from the leveling of the [Billings] canopy.” The old cracked seam on the top portion opened up and had to be cemented again.

“Beneath this top piece was found a number of granite ‘pinners’ with some cement which had served in 1880 to bring the stone to a level and under these was the rest of the rock, which people previous to 1880 will remember showed through a small space in the flooring of the canopy, and to tread on it, one had to step down a few inches. Probably less than seventy-five people watched the removal.”

– Frederick W. Bittinger, The Story of the Pilgrim Tercentenary Celebration (Plymouth MA, 1923), 24.

The Rock was housed in a brick building on Water Street, and then dragged on rollers, using tackle, to the shoreline site. A heavy granite foundation was placed under the Rock in its adjusted shoreline location because of its sandy soil.

A new neoclassical portico to house the Rock, designed by McKim, Mead and White and donated by the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, was constructed of New Hampshire granite and dedicated on November 29, 1921.