History of the Museum

Built in 1824 by the Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall is one of America’s earliest public museums. The Society was incorporated in 1820 during the 200th anniversary of Plymouth Colony’s founding, to commemorate the history of the Mayflower Pilgrims. Although most of its founders were Pilgrim descendants, the Society was open to any who shared an interest in preserving Plymouth history.

The organization’s charter laid out the ambitious goals of

procuring in the town of Plymouth a suitable lot, or plat of ground, for the erection of a monument to perpetuate the memory of the virtues, the enterprize and unparalleled sufferings of their ancestors, who first settled in that ancient town; and for the erection of a suitable building for the accommodation of the meetings of said associates…1

DETAIL

Henry Sargent, The Landing of the Pilgrims, 1818 – 1824.

PHM 0039 Gift of the Artist

By spring 1822, the Society had raised enough money to purchase a lot on Court Street with a balance of $4,000 to begin construction of a building. It was to be sufficiently grand to house a monumental history painting, The Landing of the Pilgrims, recently completed by American artist Henry Sargent (1770-1845) and promised for exhibition. The proposed Hall would also include assembly areas, and a “suitable room for antiquities which may be collected by the Society and for a Library.”2

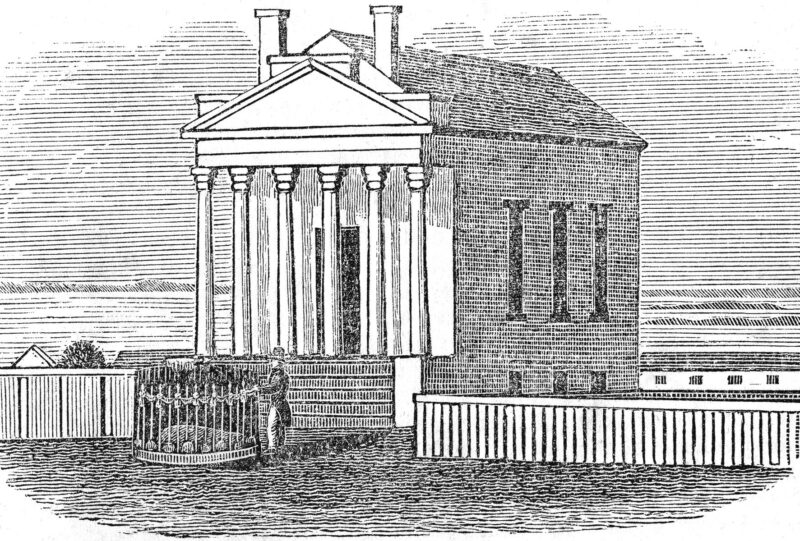

The Society engaged architect and engineer Alexander Parris (1780-1852) to create a stately edifice in the new neoclassical style. His plan for Pilgrim Hall was a monumental stone temple with a columned granite entrance in the plain Doric order. Despite its austere design, the cost to the newly formed organization was a staggering $10,000. The cornerstone was laid on September 1, 1824, during which documents, coins, and an engraved plate were among the items placed inside the cavity.3

Jacob and Abner S. Taylor of Plymouth were the master builders and masons hired for the construction. They used high-quality materials including split granite quarried from nearby Weymouth, Massachusetts, and timber transported from Maine.

Parris’s design was not fully executed due to the daunting expense. As first completed, the early Hall was a seventy by forty-foot unadorned, pitched-roof box without the impressive stone entrance envisioned by Parris. The Taylor brothers finished the simplified structure in time for the annual celebration of Forefathers Day in December 1824, that featured an address by Harvard College’s famed orator, Edward Everett.4

The Hall’s main façade remained exposed red brick until contractors added a granite facing a decade later. In the 1830s, the Society considered implementing Parris’s granite portico but balked at raising an additional $10,000. Instead, they commissioned architect Russell Warren of Providence, RI, to design a wooden version with six 24-foot-high fluted Doric columns. Finished with textured paint to resemble stone, Warren’s design cost only $1,000 and remained until finally replaced with stone in 1920.5

A rare description of Pilgrim Hall’s interior spaces appeared in Englishman J. S. Buckingham’s account of the 1838 Forefather’s Day Ball held in the two-story upper hall. The author estimated a crowd of 400 people at the event, describing the venue as

lofty and well proportioned, lighted [by windows] on both sides. At its entrance are two ante-rooms, used for the Library and Museum; and above these two are two drawing rooms, communicating with the orchestra or gallery, which are used for refreshments.6

On Independence Day, 1834, Pilgrim Hall became the new location for the top half of Plymouth Rock. The upper portion of the historic boulder was carted in a public procession from the Town Square (where it had been placed next to the “Liberty Pole” in 1774 as a symbol of patriotism) and ensconced on the museum’s front lawn. An important attraction for visitors to Plymouth, the Rock was provided with a wrought iron enclosure, embellished with swags, the names of the signers of the Mayflower Compact, and scallop shells, an ancient symbol of pilgrimage.7

In 1836, a group of women in the Pilgrim Society held a fair to raise money for interior improvements to the Hall: a chandelier for the Assembly Room; grates, fenders and fire sets for the building’s five fireplaces; masonry, carpentry, papering, and painting; a railing for Colonel Sargent’s picture, and “sundry articles of furniture.”8

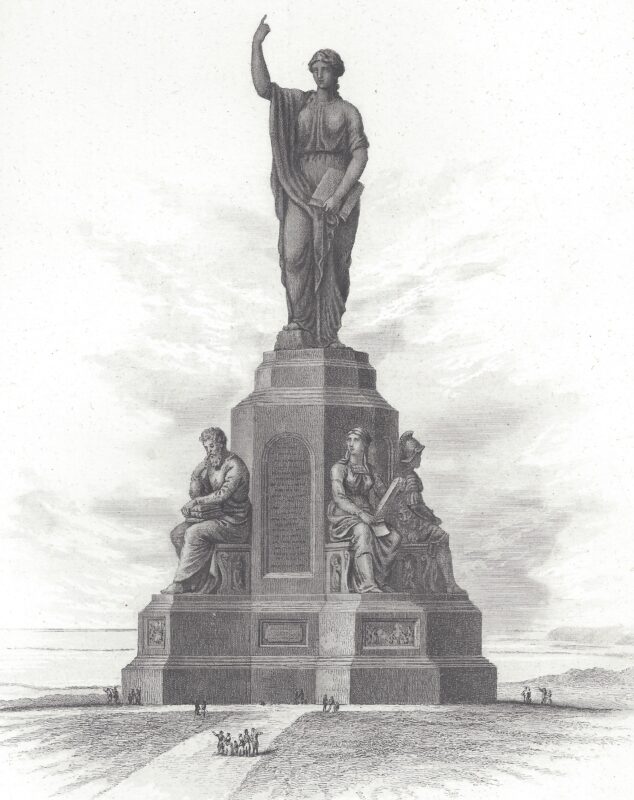

At mid-century, the maturing organization embarked in earnest on the monument building that had been part of its original purpose. The Society developed plans for a massive National Monument to the Forefathers as well as for a granite canopy to be placed over the portion of Plymouth Rock still embedded on the waterfront. In 1855, the Society commissioned architect and illustrator Hammatt Billings (1818–1874) for both projects after he offered to raise the funds himself if his designs were accepted. The cornerstones for both structures were laid with fanfare in 1859 but progress halted during the Civil War.

Billing’s Italianate canopy over the Rock was eventually completed in 1867. Measuring thirty feet high and fifteen feet square, it was built so snugly around the base of the Rock that a section had to be sliced off for the dressed masonry to fit together.

The original design for the Forefathers Monument envisioned by Billings ultimately had to be reduced by half. The scaled-back version was a monumental 81-ft. in height with a colossal solid granite figure of Faith at its center, completed and dedicated in 1889. The Society eventually deeded these historic properties to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as in 1993 most of Coles Hill, a significant waterfront area which they had acquired parcel by parcel over the years to preserve the burying places of Mayflower passengers who died during their 1st winter in Plymouth.

In 1880, Joseph Henry Stickney (1811–1893) of Baltimore, who summered in Plymouth and had joined the Pilgrim Society, funded extensive renovations to protect Pilgrim Hall from fire risk. The alterations furthered the Society’s goal of securing gifts of early artifacts and Pilgrim-related materials with confidence of their safe storage.9 Workers installed marble wainscoting, windows and doors clad in metal, and sealed off the orchestra gallery, with access via an iron staircase enclosed behind the wall.10 They also placed large monitor-style skylight and ventilator along the east-west axis of the roof to provide light and air. These changes allowed windows on the north and south walls of the Main Hall to be filled in with stone, creating additional wall space for the Society’s growing collection of historical artworks. In 1914, this rooftop installation was replaced with a copper-clad skylight running nearly the full length of the main building roof.

During the Stickney period, Plymouth Rock was moved from the Museum in 1880 to be reunited with its bedrock on the waterfront, and “1620” carved into its surface. About the same time, a wooden sculptural group depicting the 1620 landing of the Pilgrims was placed in the tympanum of Pilgrim Hall’s wooden portico.

No surviving records document the commission or installation of the sculpture, but photographs indicate its presence by the early 1880s. By 1909, the sculptural group had been dismantled and subsequently vanished after removal. One element of it, the bust of Squanto, turned up decades later in a New York antique shop and rejoined the Museum’s collection.11

In the early 20th century, the Society added a two-story granite library wing on the north side of the building to house its collection of early Plymouth papers, manuscripts, and other archival materials and publications. The addition was designed by the Boston architectural firm of Henry W. Hartwell, William C. Richardson and James Driver. Modestly set back from the main building and ascending to the eave line of the original Hall, it opened to the public in 1905. The upper level formed a spacious library and reading room with a vaulted Guastavino-tiled ceiling and terrazzo floor, lined with bronze-patinated steel book shelving fitted with latticed doors. The east and west façades of the wing’s upper story were broken by three large copper-framed windows to allow natural light for readers.

The vaulted lower floor served a range of purposes, and today houses the Museum’s archives and curatorial offices.12

After the completion of the Library wing, Pilgrim Society members became instrumental in planning the Tercentenary Celebration of 1920, including additional changes to Pilgrim Hall. The New England Club of New York donated a granite portico for the building, designed in the manner of Alexander Parris by the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White, to replace the economical wooden portico. Mary Louise Goodhue (c1876-1965), who had taken over the work of her late husband Harry Eldredge Goodhue, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, stained-glass maker, designed a series of stained-glass windows for the front of the Library. The Daughters of Founders and Patriots of America, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Chapter funded Goodhue’s windows depicting the Mayflower, Pilgrim families, and Plymouth’s wooded shoreline. 13

An ornamental water fountain was erected on the grounds by the General Society of the Daughters of the Revolution and dedicated on September 20, 1921. Originally placed in a small garden located behind the Museum building, it was moved to the front yard when the garden was converted into a museum parking lot in 1963. The ornate bronze replica Mayflower that adorned the top of the fountain was stolen in November 1966 and never recovered.14

By the early 21st century, the need to modernize and expand the historic complex became imperative. In 2003-2007, a capital campaign supported the addition of a two-story wrap-around wing, designed by architect and Pilgrim Society Trustee, Christopher Hussey.

Completed in 2008, the new wing added an exhibition gallery and collections storage area and introduced climate control to the facility for the first time. The glass-fronted addition enclosed the 1905 Library; its stained-glass windows were backlit to create a dramatic reception area and allow passersby to enjoy Goodhue’s artistry from the street.15

The 21st century renovation was accompanied by a comprehensive exhibit redesign which incorporated new areas on Wampanoag history to provide a more complete and accurate view of early Plymouth Colony. In 2018, the Museum’s first exhibition devoted entirely to Indigenous history, Wampanoag World, was co-curated by Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribal member Linda Coombs and Executive Director Dr. Donna Curtin. In 2019, the Wampanoag-owned production company SmokeSygnals produced a film series on Wampanoag and Mayflower women’s voices for a special exhibition, PathFounders: Women of Plymouth. In 2021, the Board of Trustees approved the creation of a Wampanoag Advisory Council to broadly review and advise the Museum on historical and educational activities on an ongoing basis. The group formed in 2022 with members of the Mashpee, Aquinnah, and Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribes, along with an Indigenous scholar-in-residence.

Pilgrim Hall Museum’s venerable history is reflected in the eclecticism of the architectural styles and materials used in building episodes spanning three centuries. Interpretively, this two-hundred-year-old institution has been a resource for generations of inquiry into the history of Plymouth, Massachusetts and continues to foster evolving understandings of this significant past. While the Museum has changed over time, Pilgrim Hall remains an iconic American institution dedicated to telling the story of Plymouth.

By Donna D. Curtin and Connor Gaudet

Previous institutional histories that inform this work:

Peggy M. Baker, “Pilgrim Hall Museum: An Honorable Past, a Glorious Future!” (Pilgrim Hall Museum, 2010); Jane Port and Stephen O’Neill, “Plymouth’s Pilgrim Hall: America’s First Public Museum,” unfinished draft (Pilgrim Hall Museum, nd).

END NOTES

1 Charter of the Pilgrim Society, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, January 24, 1820. Emphasis added.

2 Minutes of the Pilgrim Society, Vol. 1819-1890, September 22, 1821, Pilgrim Society Archives, Box 3.

3 James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth (Yarmouthport: Parnassus Imprints, 1972, 3rd edition with an introduction by The Reverend Peter Gomes), 245; John Warner Barber, Historical collections….of every town in Massachusetts (Worcester: Dorr, Howland & Co. 1839), 518-519. No actual plans or drawings for Pilgrim Hall have been found in the Society’s archives or among Parris’s papers.

4 William T. Davis, History of the Town of Plymouth (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis & Co., 1885), 173-174; “Pilgrim Hall,” Old Colony Memorial, Vol. 3, No 19 (September 4, 1824), [2] and “Pilgrim Hall – From the Boston Daily Advertiser,” Old Colony Memorial Vol. 3, No 34 (December 11, 1824), [2-3]; Edward Everett, An Oration Delivered at Plymouth, December 22, 1822 (Boston: Cummings, Hilliard & Co., 1825).

5 Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth, 244; Organizational Records 1818-1859, March 1, 1834, Pilgrim Society Archives, Box 1.

6 J.S. Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic, and Descriptive (London: Fisher, Son & Co., 1841), Vol. III, 570-571.

7 The rock split during the effort to remove it to Town Square in 1774, and the lower half remained in its original bed. For the most complete history of the Rock, see James W. Baker, Plymouth Rock’s Own Story (Plymouth, MA: Pilgrim Society, 2020); also Rose T. Briggs, Plymouth Rock: History and Significance, (Boston: The Pilgrim Society, 1968), 7-8, 16; “Forefathers Rock,” Old Colony Memorial, Vol. XIII, No. 13 (July 12, 1834), [2]; Organizational Records 1818-1859, November 20, 1835, Pilgrim Society Archives, Box 1.

8 Organizational Records 1818-1859, James Thacher’s report to the Pilgrim Society, June 1836, Pilgrim Society Archives, Box 1.

9 Davis, History of the Town of Plymouth, 173-174.

10 This upper area was renovated in the 21st century with steel-and-concrete construction to accommodate an HVAC system and storage space.

11 “It is Missed,” Old Colony Memorial, Vol. 88, No. 45 (November 6, 1909), 4.

12 Hartwell, Richardson & Driver had been the architects of Plymouth’s First Parish Church constructed in 1895. The R. Guastavino Company of New York, whose founder, Rafael Guastavino (1842-1908), immigrated to the United States from Spain in 1881, created vaulted ceilings for many distinguished buildings, including the Boston Public Library, and Grand Central Station and the Immigration Station on Ellis Island in New York. See The Old World Builds the New: The Guastavino Company and the Technology of the Catalan Vault, 1885-1962, Janet Parks and Alan G. Neumann (New York: Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, 1996).

13 “Stained Glass Windows Designed by a Woman,” Cambridge Tribune Vol. XLIII, No. 21 (July 24, 1920).

14 Frederick W. Bittinger, The Story of the Pilgrim Tercentenary Celebration at Plymouth in the Year 1921 (Plymouth, MA: The Memorial Press, 1923), 123-24; Pilgrim Society Annual Meeting Report, December 21, 1963; Executive Committee Minutes, December 1, 1966, Pilgrim Society Archives.

15 Peggy M. Baker, “We Did It! Pilgrim Hall Reopens,” Pilgrim Society News (Summer 2008), 1, 4-5.