Witchcraft in Plymouth Colony

“Mehittable Warren is a Witch”

By Emily Czirr

Originally published in Pilgrim Society News (Fall 2012): 6-7

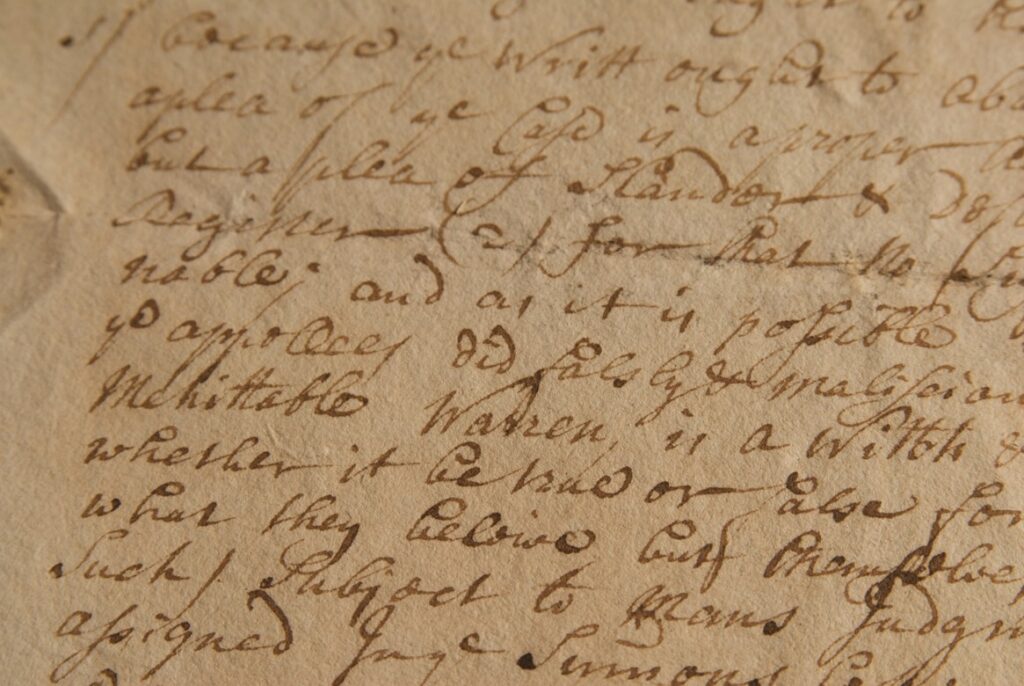

Detail, Appeal of John and Joseph Morton to the Superior Court of Judicature, March 1709, Pilgrim Hall Museum Archives

As autumn approaches, thoughts of falling leaves, apple cider, and pumpkin picking begin to fill the air. Many people also start to think about Halloween and the eerie topics of ghosts, zombies, and vampires. Witches are another popular subject this time of the year and many people travel north of Plymouth to Salem each October to participate in witch-related festivities and remember the Salem witchcraft hysteria of 1692.

What many people might not realize, though, is that Plymouth has its own history of witchcraft cases. In the 17th and 18th centuries there were three recorded witch accusations in Plymouth, and Pilgrim Hall Museum possesses a document connected to one of these trials.

In 1708, Mehitable Warren of Plymouth was accused of being a witch. Born in Hingham, Massachusetts to Edward and Elizabeth (Eames) Wilder in 1661, she was their seventh child and grew up with four brothers and six sisters. Mehitable lived in Hingham for most of her life and only moved to Plymouth after she married Joseph Warren, descendant of Mayflower passenger Richard Warren, in December 1692 (the same year as the infamous Salem witchcraft trials). They had three children: Joseph (born and died December 1693), another Joseph (born January 1694), and Priscilla (born June 1696 and died after June 21, 1716). Mehitable became a widow when her husband Joseph died in December 1696; she continued to live in Plymouth for several more years, but eventually moved back to Hingham before her death, which occurred sometime after 1716.

Before she left Plymouth, Mehitable was verbally, but not legally, accused of being a witch by John and Joseph Morton. These two brothers were the sons of Ephraim Morton Jr., and descendants of George Morton, presumed to be the Mourt of Mourt’s Relation, and passenger on the Anne in 1623. The court records of Mehitable’s trial have been lost, but from the document at Pilgrim Hall, and appellate records, we know basic details about her case.

It appears that she sued the Morton’s for defamation in September of 1708. A series of appeals followed from both the plaintiff, Mehitable, and the defendants, John and Joseph. Pilgrim Hall’s document is the original appeal made by the Mortons to the Supreme Court of Judicature in March 1709 and it details the reasons why the Mortons were unhappy with the defamation accusation.

The Mortons took many aspects of the case and attempted to turn it against Mehitable. She sued the Mortons for “Slander & Defamation,” but the Mortons argued that this specific choice of words was not a proper accusation because they claimed it was not listed in the Court’s register. They argued that the official accusation should have been “scandolous words Spoken,” and because she did not use this phrase, the results should legally not stand. This is an interesting argument, especially since the terms slander and defamation had been used in prior witchcraft cases in New England. In his book Entertaining Satan, historian John Demos refers to a 1669 case where a man from Haverhill, named Godfrey, sued a Daniel Ella for defamation, because Ella had said Godfrey was seen in two different towns at the same time. Similar to Mehitable’s case, this trial was based on a verbal accusation and also involved the concept of witchcraft. Since lawyers were uncommon at the time, did the Mortons know that defamation had been used in earlier Massachusetts trials related to witchcraft accusations? They had clearly done some research before their appeal, since they cited the absence of slander and defamation as legal terms in the court register, but did they not look closely enough?

Another reason given for an unjust ruling was that the Mortons were found guilty of “falsely & maliciously” stating that she was a witch. But, since it was their own opinion that she was a witch, they argued that their personal beliefs could not be judged by another person, and that such beliefs could also not be proven to be correct or incorrect by another, because an opinion only belonged to whoever stated it. But, wouldn’t sharing a cruel opinion such as this one in conversation count as the “scandolous words Spoken” that they argued should be the basis of the trial anyway?

Although this legal paper is not a record of Mehitable’s whole lawsuit, nor her own appeal, the fact that it is the Mortons appeal still gives us information about the case and witchcraft accusations in early 18th century New England. But of course I’m not going to reveal all of the secrets about witchcraft in Plymouth here. If you are curious to know more about Mehitable’s trial, more details about the Mortons appeal, and want to learn about the two 17th-century witchcraft cases, make sure to come hear “Wickedly & Maliciously”: Mehitable Warren and Witchcraft in Plymouth on October 29 at 7pm at Pilgrim Hall Museum. And be sure to stop in and see this witchcraft document on display from mid-September through the end of December [2012] in Written, Printed, & Drawn: Rarities from Plymouth’s Past.