The Sparrow-Hawk

Shipwreck, Oak and Elm

England, Early 17th Century

PHM 0605 Gift of Charles Livermore, 1889

One of the most intriguing objects in the Museum collection is a shipwreck, the 17th century remains of a wooden vessel known as the Sparrow-Hawk.

Only about a third of the size of the Mayflower, the vessel is believed to have transported about 25 young men and women, mostly Irish, across the Atlantic Ocean bound for Virginia until wrecked off Cape Cod in 1626. The stranded travelers found shelter in Plymouth Colony for almost a year. They eventually arranged for passage to their original destination, leaving behind controversy and the remains of their ship buried in the sands off Orleans.

In 1863, a great storm churned up the wreck, igniting interest in a unique relic of early colonization. Reassembled and given a name, the Sparrow-Hawk was shown in Boston and other cities until donated to Pilgrim Hall Museum in 1889, where it was a prized attraction for over a century.

Over the years, the Sparrow-Hawk has been displayed at various times and places, and was recently the subject of scientific study in preparation for a comprehensive exhibition that recounts the story of the vessel, its perilous voyage, and New England’s first Irish immigrants.

“Ther was a ship, with many passengers in her and sundrie goods, bound for Virginia.“

– William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation

About 400 years ago, in 1626, a vessel making its way to Virginia was forced off course and damaged in a storm, which drove the ship onto the eastern shore of the Cape Cod peninsula, Massachusetts. Onboard were two English merchants, John Fells and John Sibsey, and a company of servants and farmers bound for Virginia, many of whom were Irish. The ship was damaged beyond repair in a storm and was driven ashore.

They had lost them selves at sea, either by ye insufficiencie of ye maister, or his ilnes; for he was sick & lame of ye scurvie…. they came right before a small blind harbore, that lyes about ye midle of Manamoyake Bay, to ye southward of Cap-Codd, with a small gale of wind; and about highwater toucht upon a barr of sand…. But towrds the evening the wind sprunge up at sea, and was so rough, as broake their cable, & beat them over the barr into ye harbor, wher they saved their lives & goods…

– William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation

The passengers and crew were helped by the Indigenous Nauset people, then sheltered by the English colonists at Plymouth for nearly a year while they awaited passage south. Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford, who assisted in rescuing the stranded party, documented the story of the shipwreck in his 17th-century journal of the settlement’s early years.

Over time, the ship’s remains vanished from sight and from local memory, until a brief reappearance on a tidal flat off the coast of what is present-day Orleans and Chatham in 1782. Shifting sands and coastal marsh covered it up again until many years later, a great storm churned up the old wreck once more from its long-forgotten resting bed in 1863.

On May 6, 1863, Solomon Linnell 2nd, and Alfred Rogers were walking along the tidal marshes on the Pleasant Bay side of Nauset Beach. They found the remains of an ancient shipwreck uncovered by a storm a few days earlier, sticking up out of the mud. The remnants were a mile from navigable waters and looked to be of great antiquity.

Curious locals trekked their way down the beach or across the Bay to the site, making off with many “souvenirs.” Leander Crosby of Orleans visited the wreck on May 9, and found ballast stones, beef and mutton bones, leather soles of shoes, pipe stems and even a metal box. Two other visitors, Dr. B. F. Seabury and John Doane found the rudder some distance away. The rudder was taken away to be placed on display in the Exchange on State Street in Boston.

Amos Otis, a genealogist and Cape Cod historian from Barnstable, paid the site a visit, taking detailed notes, measurements and drawings of the wreck. Otis also interviewed many of the locals, who had referred to the area for generations as “Old Ship Harbor.” The ship’s remains were covered up again with sand and left where they were found.

Amos Otis published two articles in the New England Historic and Genealogical Register, which were later republished as the booklet An Account of the Discovery of an Ancient Ship on the Eastern Shore of Cape Cod in 1864. Otis presented geological evidence which showed that the marshes where the wreck was found were not mentioned in records before 1750. As marshes take up to a century to form, Otis concluded that there had been no navigable water near the site since the mid-seventeenth century. He also proposed that the remains were those of the ship bound for Virginia mentioned in Governor William Bradford’s history of early Plymouth. Bradford never mentioned the ship’s name, which is not documented in any known primary source. Otis, however, mentioned an “uncertain and unreliable” local tradition “that the name of the Old Ship was Sparrow-Hawk.” One of the oldest families in the area was named Sparrow, which may have influenced the attribution.

The decision was made to remove the entire wreck when another storm uncovered the remains again in late 1864. Leander Crosby and Boston City Councilman Charles Livermore arranged to have the rescued timbers taken to the East Boston shipyard of Peter E. Dolliver and Sylvester B. Sleeper, shipbuilders, for reassembly. Dennison J. Lawlor, a noted designer of schooners, drafted the ship’s lines and built a model. Crosby and Livermore published a booklet, The Ancient Wreck, Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, Remarkable Preservation and Recent Discovery of the Wreck, in 1865. This booklet repeated much of Amos Otis’s earlier study but this time refers to the wreck as the “Pilgrim Ship Sparrow-Hawk.”

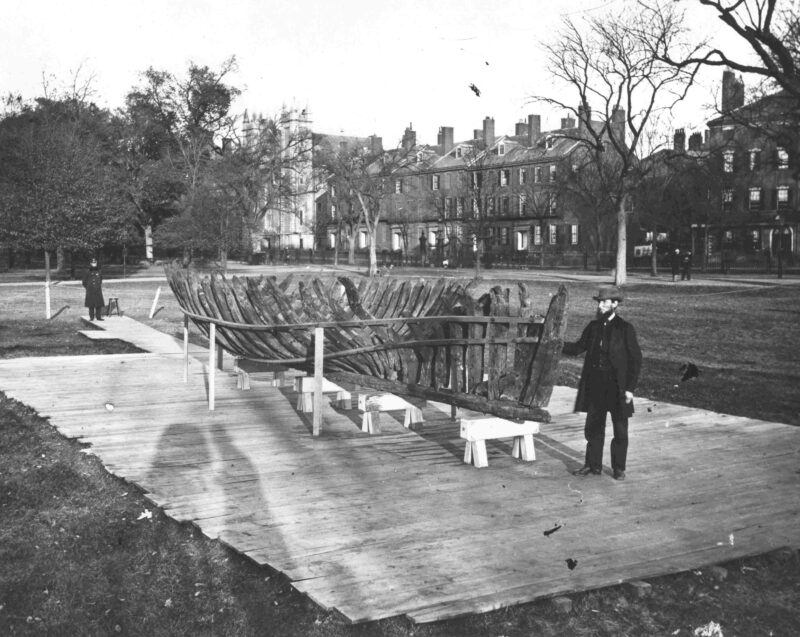

Leander Crosby and Sparrow-Hawk on Boston Common, 1865

Leander Crosby and Charles Livermore put the reassembled Sparrow-Hawk on display on Boston Common in September and October of 1865. Thousands of visitors came to inspect the “Pilgrim Ship Sparrow-Hawk” as it was then called. Members of the Massachusetts Historical Society discussed the ship in their meetings and published reports about the vessel.

Thomas Southworth, one of the earliest and most important American photographers, took a picture of Leander Crosby standing with the Sparrow-Hawk while it was on the Common. Southworth photographed most of the historic and interesting sites around Boston. The photograph of the Sparrow-Hawk shows its location near the West Street gate on the Tremont Street side of the Common.

Following the Sparrow-Hawk’s display on Boston Common, Charles Livermore took the vessel’s remains to a storehouse in Providence, Rhode Island. He brought a few personal friends around to inspect the ship, but after that, the Sparrow-Hawk remained in storage,

apparently forgotten. In 1889, Charles Livermore wrote to the Massachusetts Historical Society for their advice as to where they thought the Sparrow-Hawk belonged. They recommended Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth, where the rudder was already on display.

Acquired by Pilgrim Hall in 1889, the Sparrow-Hawk has been one of the Museum’s most intriguing artifacts for generations. Exhibited for many years in the original hall, the shipwreck became the focus of special researchers investigating the design and construction of 17th-century ships.

The Museum created a special “Seventeenth Century Ship Room” on its lower level in 1952. At the same time, H. Hobart Holly, an employee of the Quincy, Massachusetts shipyards, published the “Sparrow-Hawk: A Seventeenth Century Vessel in Twentieth-Century America” in The American Neptune magazine. His article was twice republished as a booklet. Holly examined the technical aspects of the Sparrow-Hawk’s construction. He identified many of the construction techniques in the ship that dated from sixteenth and seventeenth century shipbuilding.

William Avery Baker was also an employee of the Quincy shipyards and later the Curator of the Hart Nautical Collection at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His interest in historic ship design made him the foremost expert on the construction of colonial and early American ships. He used the Sparrow-Hawk as source material when designing the Mayflower II, drafting plans for the replica which was built in England and has been berthed in Plymouth Harbor since 1957. Baker continued to investigate the Sparrow-Hawk for decades to identify what type of vessel it was. In an essay for the Pilgrim Society in 1980, he concluded the Sparrow-Hawk was an English bark of two masts: a mainmast with mainsail and topsail, and a foremast with square- sail.

The size of the Sparrow-Hawk was typical for many ships of the seventeenth century that made the Atlantic crossing.

| Sparrow-Hawk | Principal Dimensions |

| Length overall | 40 feet |

| Length of keel | 28 feet, 6 inches |

| Breadth | 12 feet, 6 inches |

| Depth | 8 feet |

| Loaded draft aft | 7 feet (approx.) |

| Tonnage | 36 tons (approx.) |

| Complement | 25 people |

The Sparrow-Hawk shipwreck has been studied by maritime experts, assembled and disassembled, measured, drawn, and exhibited many times, but was never fully examined archeologically or forensically until 2018. At that time, one big question still haunted the huddle of salt-worn timbers: were they, in fact, from the same vessel described by William Bradford that brought the first documented Irish colonists to New England?

In 2018, Pilgrim Hall Museum embarked on an in-depth scientific analysis of the remains in an effort coordinated by Dr. Calvin Mires of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and Bridgewater State University. Led by Dr. Frederick Hocker, Director of Research at the Vasa Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, and Associate Professor Aoife Daly, Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen, the research team extracted samples for scientific analysis, to discover whether the vessel was indeed a European ship from the 17th century.

Using a combination of several analysis techniques, researchers sought to identify the date range and provenance of the ship timbers. Initial dendrochronological analysis was inconclusive. But radiocarbon wiggle-match dating of the timbers from the Sparrow-Hawk demonstrated that the remains are from a ship built of trees that were felled in the decades on either side of 1600, from the late 16th century to the early 1610s.

Revisiting the dendrochronological evidence, the researchers found that the planks’ tree-rings match with English tree-ring chronologies, confirming an English origin of the timbers. The physical remains of this English-built early 17th-century colonial vessel, extracted centuries after its transatlantic crossing from the salt marshes of Cape Cod, can now be said to conform closely with Bradford’s historical account.

The team’s finding were reported in an article, “Dating the timbers from the Sparrow Hawk, a shipwreck from Cape Cod, USA,” in the Winter/Spring 2022 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. The analysis is the first step in understanding the oldest known shipwreck of English Colonial America and adding new details to the compelling story of Plymouth Colony’s founding and the arrival of the European settlers in New England 400 years ago.

This content is based on previously published material by the Pilgrim Society and Pilgrim Hall Museum.